Planners must think backward from the target to optimize the kill chains used to attack.

The kill chain competition is among the foundational struggles of every military conflict. Adversaries compete in capabilities, capacity, geography, and industrial and financial resources can shift the balance of power in conflict from one side to the other, which is why these are priorities in both peace and war. No competition, however, is as central as the command and control kill chains that deliver weapons on targets. Should kill chains break at scale, it can lead to the catastrophic loss of a conflict.

Kill chains are not just as an abstract concept, but rather is made up of physical sensors, datalinks, platforms, and weapons, each with its own tangible characteristics and limitations. Each also has specific informational, physical, and network requirements. For the U.S. Air Force to maintain its kill chain advantage, it must evolve its kill chains to counter adversary strategies to break them.

Planners must think backward from the target to optimize the kill chains used to attack it. Target characteristics dictate which platforms, sensors, and capabilities planners use; nodes that perform similar functions but have different characteristics may not be interchangeable. The type and precision of the sensors used to locate and track a target, the type of weapon and effect, and even the bandwidth and latency of the kill chain’s datalinks must be tailored to the target and mission.

This is why kill chains the Air Force developed over the past 20 years for operations in the Middle East are insufficient for a peer conflict in the Pacific. Many of the Air Force’s current kill chains are insufficient for the geography of the Indo-Pacific and the threats posed by China’s modernized People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

In the Middle East, a flight of F-16s could loiter for hours in a kill box, waiting for a weapons release order from the joint force air component commander in the nearby air operations center (AOC) with relatively low risk. That won’t be possible over Taiwan, where communications will be contested, and aircraft will be hundreds of miles from the nearest air operations center. Loitering there would likely prove fatal.

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall’s Operational Imperatives aim to create the capabilities needed to conduct effective operations in that fight.

Kill chains must also be able to withstand adversary attacks, which can be either defensive or offensive in nature. Defensive attacks consist of Area Access/Area Denial threats that force non-stealthy U.S. platforms to operate beyond useful ranges for sensing or weapons delivery; camouflage and decoys intended to cause U.S. forces to waste weapons; or “shoot-and-scoot” tactics intended to deny the U.S. the ability to gather precise target data.

Offensive attacks include jamming or disabling space constellations in low-Earth orbit, destroying command nodes like AWACs, or jamming Link-16 and other datalinks to isolate U.S. platforms and prevent them from sharing information to progress the kill chain.

China’s “System Destruction”

China has ardently studied how the U.S. military conducts combat operations, starting with the U.S. military’s ability to successfully close kill chains at war-winning scale, speed, and scope during Operation Desert Storm. That experience drove the PLA to change from a warfighting concept that seeks to achieve victory by attriting opposing forces to “system destruction warfare.” This warfighting concept deliberately seeks to disrupt, degrade, and destroy the system of systems that defines the U.S. operational architecture. The PLA seeks to destroy kill chains by attacking U.S. sensor networks, datalinks, and command and control (C2) architectures, and other nodes. This strategy seeks to dismantle the pillar of America’s asymmetric advantage in combat—the system of systems that U.S. forces rely on to conduct modern warfare.

Legacy military kill chains are linear and vulnerable to China’s system destruction warfare, which put every step of U.S. kill chains at risk—from sensors to shooters to the networks that connect them and the data they share. The very technologies that make the U.S. kill chains so efficient and effective makes them more vulnerable to system destruction warfare—especially if assets required to complete multiple kinds of kill chains are only available in limited numbers.

For example, an airborne AWACS or future implementation of today’s JSTARS (Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System) might support multiple steps in multiple kill chains. Without enough, the loss of such high-demand, low-density nodes could cripple the U.S. military kill chains, slowing the pace and scale needed to achieve a theater commander’s objectives.

The risk to the force from this vulnerability is amplified by the fact that the Air Force today lacks the force size needed for peer conflict.

Ripe for Change

Since the mid-2000s, the Air Force’s combat aircraft inventory has been the smallest and oldest in its 76-year history as a separate military service. To compensate, the Air Force has made its kill chains more efficient and effective by leveraging advanced technologies, such as high-speed computer processing and datalinks. These enhancements maintain lethality even as the combat force shrinks. These new kill chains were optimized for theater contingency operations and low-intensity conflict in the permissive environments exemplified by Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, Inherent Resolve, and other similar fights involving non-peer adversaries—those without sophisticated means to systematically disrupt U.S. kill chains. The dynamic and fleeting nature of high-value targets in these conflicts drove the Air Force to develop means to initiate and close kill chains in a matter of minutes and with precision.

In a peer conflict, however, kill chains will have to engage dynamic and fleeting targets at a scale, scope, and speed unprecedented in modern warfare.

What is a Kill Chain?

A kill chain is the process used to put Air Force missiles or bombs on target. The Air Force breaks the kill chain down into six discrete steps: find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess. Since the late 1990s, Airmen have used this “F2T2EA” model to find and destroy targets and to understand the relationship between the sensors, platforms, and weapons employed to close those kill chains.

Find. The first step of any kill chain is to find the target. Surveillance operations study battlespace to detect and characterize potential targets.

Fix. Once a potential target is found, targeting data passes to one or more sensors to “fix,” or locate its position relative to the rest of the battlespace, and then to positively identify it—with sufficient fidelity to engage it with weapons—as the desired target.

Track. Targets’ location and identity must be continuously tracked—what warfighters call maintaining “positive custody.” If positive custody of a target is lost, the kill chain is broken, and the process must revert to an earlier step.

Target. When it’s time to engage, targets are assigned based on the specific requirements for each target. A mobile target requires a different solution than a bunker buried beneath the ground, for example.

Even after a target is attacked, the kill chain continues. Sensors must be assigned to assess the damage and determine if additional munitions are necessary.

According to one former defense official, roughly 80 percent of targets in the early phase of a Chinese fait accompli invasion of Taiwan are anticipated to be mobile or quickly relocatable. Detecting these targets and initiating the kill chain will require ISR assets to be in the right place at the right time continuously, searching for and detecting moving targets. Strike forces will have just minutes or less to complete kill chain before targets relocate or take steps to negate attacks.

The scale of the battlespace and unprecedented volume of potential targets in a conflict with China pose complications, as thousands of kill chains must be closed against thousands of targets simultaneously across thousands of square miles of ocean and landmass. With limited resources to cover so much geography and so huge a volume of targets, every ISR asset, weapon system, and platform in the battlespace will be needed to complete those kill chains nearly simultaneously.

Yet, it’s also clear that today’s U.S. kill chains are rigid, offering narrow and predictable options to share information with only a limited mix of sensors, aircraft, or weapons. Relationships between functional nodes are fixed, and kill chains are generally unable to adapt when elements are lost, or datalinks are disrupted. Finally, the centralized decision-making that characterized U.S. operations over the past 20 years is not scalable to the size of a peer-to-peer war in the Indo-Pacific.

Building the Future Kill Chain Advantage

The Air Force is developing new capabilities and operational concepts to create more flexible, resilient, and lethal kill chain options in the future. The Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) program is specifically intended to deliver that new capability.

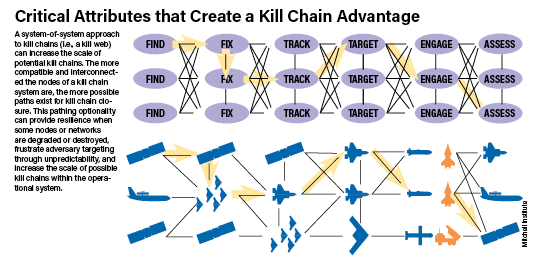

ABMS seeks to increase potential kill chain pathways across operating domains. By connecting systems and rapidly sharing information across a large network of sensors and platforms, the U.S. aims to increase the resiliency of its kill chains against Chinese countermeasures. For instance, instead of separate linear kill chains, ABMS could help create “kill webs” that operate much like self-healing mesh networks.

In this distributed or disaggregated battle network, each step in the kill chain—the find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess (F2T2EA) process—could be performed by different platforms and even, potentially, in different domains. For example, a satellite sensor might detect and find a potential target, then pass it to an airborne sensor to fix and track the target, updating and maintaining the target’s position and identification before passing it off again to a ground-based battle management node. That battle manager might then task a weapon system, perhaps an airborne bomber, to engage the target with appropriate weapons. Finally, a satellite might guide the bomber’s weapons to the designated target. Afterward, an airborne sensor conducting battle damage assessment would help battle managers determine if another engagement was required. This meshed approach makes the overall operational system less predictable and harder to counter.

Key Attributes of a Successful Kill Chain: Scale, Scope, Speed, and Survivability

Building a future kill chain that can prosecute targets as fluidly as possibly requires a focus on four measures of a kill chain’s effectiveness: scale, scope, speed, and survivability.

Scale. Increasing the number of nodes directly translates to the ability to engage more targets. Increasing the functions each node can execute also expands the number of kill chains U.S. forces can prosecute at once. This is one reason why Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has expressed a nominal intent to procure at least 1,000 uninhabited Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) to complement some 200 Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighters. Likewise, developing and deploying proliferated low-Earth orbit satellite constellations and stockpiling stores of advanced weapons will be necessary to enable the closing of the thousands of kill chains required to take on a peer rival in conflict.

Scope. Quantity is key to increasing the scope of kill chain operations because a single kill chain system, like a single combat aircraft, cannot be in more than one place at a time. The Air Force must increase the quantity of physical kill chain platforms and expand their range to achieve greater scope. Range is crucial in the Indo-Pacific, which spans 16 time zones.

Greater weapon range increases the area each kill chains can cover. Mitchell Institute analyses indicate that precision-guided munitions with ranges of 50 to 250 nm that can be delivered in large quantities by reusable stealthy fighters and bombers would not only extend the range of kill chains, but also compress the time to close kill chains, and achieve “affordable mass” for strikes against very large target sets.

Speed. The Air Force should increase the speed of weapons where feasible. Higher-speed air-launched missiles and “stand-in,” penetrating combat aircraft like the F-35 and B-21 can both accelerate kill chains by reducing the time from launch to strike.

Space-based communications, meanwhile, can also increase speed, especially when linking nodes beyond line-of-sight. The Air Force’s future low-Earth-orbit satellite transport layer will become an essential backbone for kill chains executing in highly contested battlespace. Using laser communications and native processing, LEO constellations could provide up to 350 megabits (Mbps) per second of instantaneous bandwidth to support kill chain operations, 25 times faster than today’s Link 16 terminals can deliver at a maximum of 14 Mbps.

Digital technology can also help. Developing automated tools for air battle managers and fused, accurate, and timely common operating pictures would facilitate rapid target pairing and kill chain construction. Automating kill chain functions, such as identifying and prioritizing threats and targets, pairing targets with weapons to maximize probability of kill, and efficiently managing fuel and weapons would greatly reduce air battle managers’ task saturation.

Survivability. Radar energy, heat signatures, and other emissions must be mitigated to avoid detection by adversaries’ warning and targeting systems. Datalinks featuring low probability-of-intercept/low probability-of-detection (LPI/LPD) are essential for operating in highly contested environments. Likewise, directionally focused datalinks, power modulation, frequency hopping, or even the use of new technologies, such as laser communications quantum radio frequencies may enhance overall network survivability.

Similarly, redundancy is another crucial requirement. When network nodes fail, systems must be able to heal themselves, operating less like a conventional point-to-point network, and more like a mesh of interconnected systems.

There are many factors that are moving the U.S. Air Force toward developing a more disaggregated force design, but the earliest that its warfighters could expect to see nascent versions of this future force is likely to be in the early 2030s. As aggressively as the Air Force is working to develop the technologies, operational concepts, architecture, and other enablers for ABMS, they are still not mature. The Air Force needs a bridge strategy to ensure it can achieve a kill chain advantage as it migrates into this future force.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. describes ABMS as a joint kill chain that will take “data, put it into a cloud, and then be able to access the data through applications, and not do it service by service by service.” Rather than distinct Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps kill chains, the architecture would enable all the services to leverage sensors, platforms, and weapons from any service branch to prosecute targets with the scale, scope, speed, and survivability necessary to defeat China.

Scale in this case is the capacity of an operational system to generate and close hundreds or thousands of kill chains simultaneously; scope refers to the ability of a kill chain to span great distances and operate persistently over time; speed is the ability to outpace adversary efforts to deny, disrupt, or break a kill chain; and survivability is the ability to sustain operational effectiveness under attack.

Enduring Kill Chain Advantages

During and immediately following the Cold War, the Air Force consolidated its kill chains and relied more on advanced weapons systems like the B-2 Spirit bomber F-22 Raptor fighter, which were equipped with highly advanced technologies that enabled them to initiate and close kill chains independently.

The B-2’s unique range, high payload capacity, and stealth enabled kill chains of unprecedented scope, speed, and survivability. The F-22’s supercruise, stealth, powerful sensors, and the ability to rapidly fuse sensor data gave pilots a “first look, first kill” advantage, closing kill chains against enemy fighters faster than they could respond.

While such systems have been derided as “exquisite” by critics, it is the very characteristics that made them exquisite that gave them unrivaled ability to survive and close kill chains against enemy systems independently in contested environments.

Air Force leaders should not abandon this approach. Rather, it should increase the number of fifth- and sixth-generation aircraft available to amplify kill chain advantages in scale, scope, speed, and survivability. The Air Force should accelerate its procurement of F-35s and B-21 bombers, while sustaining all its F-22s and B-2s. At the same time, it should develop advanced munitions suitable for fifth-generation aircraft; increase datalink interoperability among its platforms; and rapidly field Collaborative Combat Aircraft to increase the number of weapons available per combat sortie.

To optimize kill chain scope, fifth-generation aircraft also must be able to support both organic and off-board kill chains. The F-35’s planned Block 4 upgrade includes datalink connectivity needed to support such distributed kill chains.

Fifth-generation aircraft can finally provide survivable kill chains in high-threat and spectrum-contested battlespaces. This is an Air Force advantage that is currently unmatched by China’s PLA and other potential adversaries. To maintain this comparative advantage, the Air Force must continue to invest in improvements to its fifth-generation aircraft to offset China’s increasingly capable countermeasures.

Fifth-generation fighters will be important to the Air Force’s overall force design in the near-term as a bridge to the service’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) family of systems. Strategically, fifth- and sixth-generation combat aircraft are crucial to assure kill chain dominance because of their ability to initiate and complete every step of the kill chain process on their own.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In the near- to mid-term, the Air Force should:

- Maximize F-35 and B-21 production rates. The F-35 is the only fifth-generation aircraft in production in the U.S. today that can provide a kill chain advantage now and long into the future. The B-21, now nearing first-flight, will soon provide similar advantages. To achieve kill chain scale and scope and mitigate risk in this decade, the Air Force should maximize the rate at which it procures both aircraft.

- Aggressively invest in modernizing and improving the range and survivability of the F-35 and F-22.While developing NGAD, the Air Force can increase the survivability and reach of its existing kill chains while it works to mature the new technologies that will come with NGAD.

- Develop and produce survivable air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons suitable for fifth- and sixth-generation combat aircraft operations. Increasing the number of kill chains per sortie that fifth-generation aircraft can complete will have a direct impact on the timing and mission effectiveness of any air campaign. Enhancing survivability is key after decades of fighting in largely uncontested battlespace.

- Map out and connect the right sensors, platforms, and weapons, not necessarily every weapon. For kill chains to be highly effective, not everything needs to be connected to everything all the time. The Air Force should work to better understand which systems need to be connected when to increase the scale, scope, and survivability of its kill chains.

- Develop advanced networks and invest in connectivity across the force. Current kill chains cannot bridge most service, system, or network boundaries. Enhancing the connectivity of fifth-generation aircraft with other aircraft and strike capabilities across the force will empower both to be multifunction nodes supporting theater commanders’ kill chain operations.

- In the mid-to-far-term, the Air Force should:

- Develop automated tools to help air battle managers. Automation can enable battle managers to identify, validate, evaluate, and construct kill chains more rapidly. A disaggregated kill chain presents tremendous complexity to battle managers, especially when the physical, locational, and informational characteristics of each node are “in play.” In a highly dynamic battlespace, battle managers need automated or intelligent tools to facilitate the real-time identification of kill chain options for target pairing.

- Accelerate development of Collaborative Combat Aircraft. CCAs in quantity have the potential to be force multipliers, increasing the reach of the Air Force’s fifth- and sixth-generation aircraft and multiplying the number of targets that can be attacked. Quantity also bolsters survivability.

- Develop and launch a space-based sensing and data transport layer. High-volume sensing and communication constellations can dramatically boost the scale, scope, speed, and survivability of airborne kill chains.

- Accelerate development of NGAD and procure the aircraft quickly and in sufficient numbers to sustain the force. Cutting production too soon undermined the effectiveness of the F-22 fleet and, by extension, the Air Force’s ability to project power.

These recommendations are not “quick kill” fixes that can be achieved by simply trading off current force capacity. Yet, senior DOD leaders must consider the ultimate cost of not pursuing kill chain dominance as it develops its future force design. A defeat at the hands of a peer adversary would have devastating long-term consequences for the security of the United States and its allies and partners.