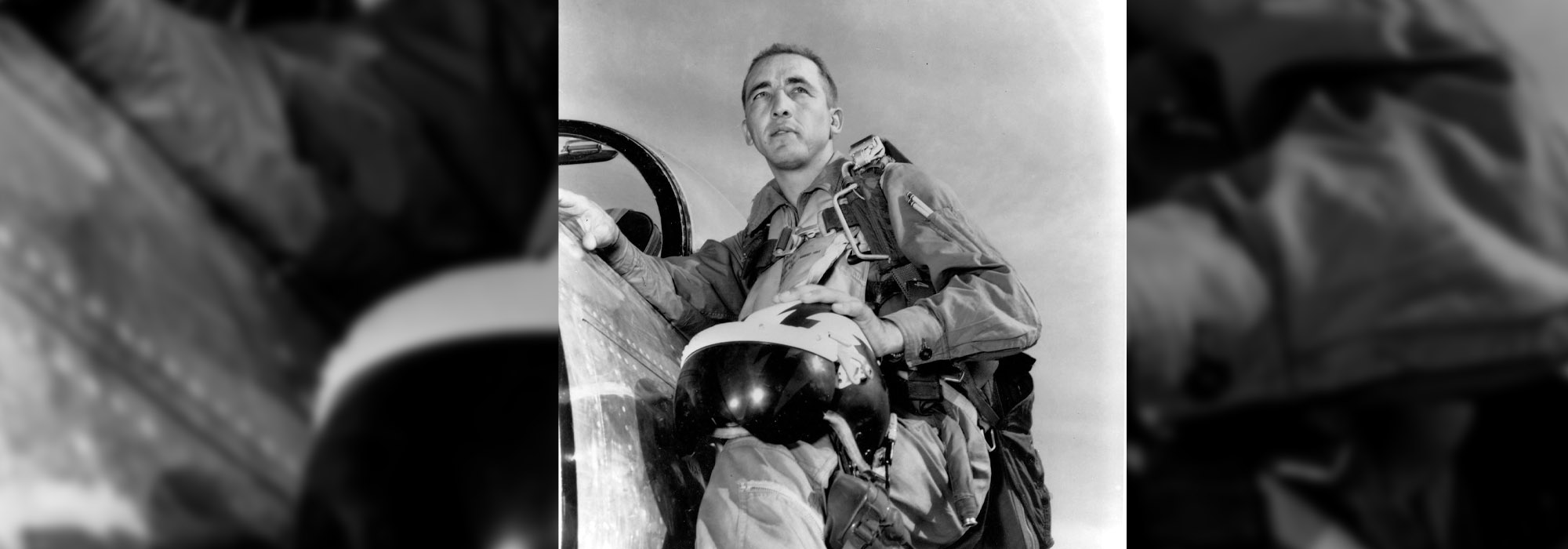

Korean War Ace Who Survived as POW.

Robbie Risner was a hero in two wars. Earning two Air Force Crosses, he was an ace in Korea and a prisoner of war (POW) in Vietnam who survived over seven years in captivity.

Raised in Oklahoma, Risner enlisted as an aviation cadet during World War II and flew P-38s in Panama. When the Korean War broke out, Risner transitioned to F-86s and was sent to Korea.

In September 1950 while escorting F-84s over North Korea he encountered MiGs. Risner chased one aircraft at low level and high speed deep into Chinese airspace. He finally caught up with his prey over Antung Airfield and shot it down. His wingman then took a fuel tank hit and began losing gas. Risner told him to shut down his engine and he would push him home. Inserting the nose of his Sabre into his wingman’s tailpipe, he began to nudge the two aircraft out over the water. Despite heavy turbulence and oil and hydraulic fluid covering his own canopy, the maneuver worked. His wingman eventually bailed out over water, and Risner, running out of fuel himself, made a dead-stick landing at Kimpo Air Base, South Korea.

He became an ace later that month and finished the war with eight victories.

Returning to the States, Risner attended the Air War College and served on a Joint Staff in Hawaii. In August 1964, Lt. Col. Risner took command of an F-105 squadron on Okinawa as the Vietnam War began to heat up. He wrote later that when he left there for the war he had a premonition that it would be a long time before he saw his family again. From Korat Air Base in Thailand, the Thuds began flying missions over North Vietnam.

In April 1965 Risner led his squadron against the Thanh Hoa Bridge south of Hanoi. The bridge was heavily defended and almost impervious to damage. Nonetheless, his determined attack earned him the Air Force Cross and his picture on the cover of Time magazine—an honor he would soon regret.

On Sept. 16 while flying against a SAM site, Risner was shot down. Captured immediately, he was moved to Hoa Lo Prison in Hanoi—the infamous Hanoi Hilton. His tiny cell was infested with rats and the food was awful, usually a thin gruel. Then the torture began. Although North Vietnam had signed the Geneva Conventions regarding the treatment of POWs, they refused to follow the rules. When Risner pointed this out, they snarled that he was not a prisoner—but a criminal who had no rights. The guards singled him out for special treatment upon seeing his picture on the cover of Time. There were repeated beatings, but the worst was the use of straps, tied tightly around his arms and then stretched back so that his elbows touched. Another strap was tied around the ankles, and this was then connected to the arms and tightened until his body was shaped like a bow. He was then usually hung from a meat hook on the ceiling. The pain was excruciating.

Other tortures were less physically painful, but hurt more psychologically. As a senior POW, it was Risner’s responsibility to agitate for better conditions for all prisoners. Doing so earned him solitary confinement and starvation. Worse, the guards boarded up his cell’s air vents and turned off his light—plunging him into total darkness for weeks at a time.

Eventually, all prisoners broke and answered questions. Risner told his fellows they should “resist until you are tortured. But do not take torture to the point where you lose your capability to think and do not take torture to the point where you lose the permanent use of your limbs.”

Risner credits his faith for surviving this ordeal. He prayed constantly: for his family and fellow prisoners, that he would endure, and that the torture would stop. He related later that his prayers were answered, and he was able to miraculously remove his shackles on one occasion when the pain was especially bad.

The Son Tay raid of November 1970 caused over 350 POWs to be moved to the Hanoi Hilton from other camps around the country to prevent more rescue attempts. Risner describes the sheer joy he and others felt at being able to see other humans and talk to them. The Linebacker strikes of later 1972 were critical. The bombs of the B-52s falling on Hanoi shook the prison guards, and the POWs knew that negotiations were producing results.

Risner went home in the first group of POWs to be released in February 1973.

He received another Air Force Cross for his leadership as a POW and was promoted to brigadier general. He retired soon thereafter to raise horses.

Risner’s memoirs, “The Passing of the Night” (Random House, 1975) are extremely moving. He died of a stroke in 2013.