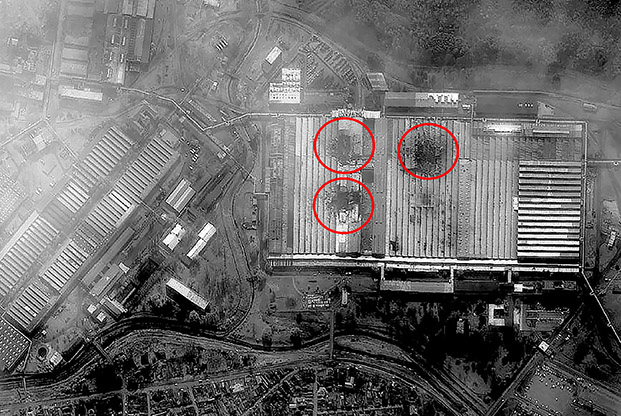

Post-strike bomb damage at the Kragujevac armor and motor-vehicle plant Crvena Zastava, Serbia. Photo: DOD

Operation Allied Force (OAF) was a NATO air campaign intended to halt a violent effort against the Kosovo Albanian population in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia by the regime of Slobodan Milosevic. NATO was initially neutral during the rise of tensions between Milosevic’s Serb-dominated government in Belgrade and the independence-minded Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) based in neighboring Albania. However, a string of KLA provocations and subsequent Serbian reprisals culminated in the Jan. 15, 1999, deaths of 45 ethnic Albanians by Serbian paramilitary forces in Racak, Kosovo. While the exact circumstances of the incident remain unclear, it served as a turning point for the US Secretary of State and other key members of the Clinton administration, who now believed that the use of force would likely be necessary to restrain Milosevic.

At meetings held at Rambouillet, France, in February and March 1999, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright presented Milosevic’s regime with an ultimatum: If the Serbs refused NATO’s demands to stop ethnic cleansing and grant Kosovo’s Albanians more autonomy, the US and NATO would respond militarily. The Rambouillet accords contained elements that were unacceptable to Milosevic. The accords granted Kosovo virtual autonomy within the Federal Republic, while its citizens would still participate in Yugoslav political institutions (including parliament, the courts, etc.); they called for a referendum in Kosovo on the question of independence (given the ethnic makeup of the population, a certainty to pass); and they gave NATO free run through all of Yugoslavia, with the duty and power to investigate and deliver suspected war criminals to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague. As Milosevic, himself, was suspected of war crimes, acceptance would have been tantamount to a surrender of not only Kosovo, but his own person. Consequently, Milosevic refused to sign the Rambouillet Accords, thus triggering NATO’s Operation Allied Force.

Slobodan Milosevic’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia regime targeted ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. Photo: NATO

PLANNING WAR … OR FORCEFUL DIPLOMACY

Clinton administration officials believed that NATO bombing would only last a few days before Milosevic would capitulate to their demands. According to USAF Lt. Gen. Michael C. Short, 16th Air Force commander and air chief of Allied Force, Washington officials told him, “Mike you’re only going to bomb for two or three nights; that’s all the alliance can stand, that’s all Washington can stand.”

Operation Allied Force was planned as a gradually escalating, three-phase air campaign. Phase 1 would target the Serbian Integrated Air Defense System (IADS) and associated SAMs and interceptors. If Phase 1 failed to intimidate Milosevic, Phase 2 would attack the Yugoslav Army (also known by its Serbian initials, “VJ”) forces deployed in Kosovo and their support structure. In a postwar interview on PBS’s Frontline, former National Security Council staffer Ivo Daalder said the administration was convinced that bombing would be sufficient to “take care of the Serb armor, their artillery, and the Serb paramilitary forces, to prevent them from doing the kind of widescale slaughter and atrocities that they would engage in.” Unfortunately, this view was out of sync with what USAF commanders believed they would be able to do in a campaign prosecuted strictly by airpower.

The third phase, if it was needed, involved widening the target set geographically to include command, control, and communications (C3) and infrastructure targets in Belgrade and throughout Serbia. At the end of each phase, a political decision would have to be made in Brussels to authorize moving on to the next phase.

US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright presented Milosevic’s regime with an ultimatum: If the Serbs refused NATO’s demands to stop ethnic cleansing and grant Kosovo more autonomy, the US and NATO would respond militarily. Photo: Helene Stikkel/DOD

ATTACK AND CONFUSION

Phase I opened on the night of March 24, 1999.

While Operation Allied Force’s stated goal was to stop atrocities on Kosovos Albanians by Serb paramilitaries, the massive Serbian “ethnic-cleansing” program to flush Albanians out of Kosovo was, in fact, triggered by NATO’s bombing campaign. While Serbian forces actually began their ethnic-cleansing campaign shortly before the NATO attack began, Milosevic gave the order to begin his operation only after NATO indicated that its attack was both inevitable and imminent. Either Milosevic saw Allied Force as an excuse to execute a previously existing plan to denude Kosovo of its Albanian population—in essence, he had nothing to lose by doing so—or he used it as a ploy to trip up NATO’s campaign. Either way, the shock from the unprecedented scale of atrocities in Kosovo (eventually, some 700,000 ethnic Albanians were driven from the province) swiftly led to a shift in NATO targeting from Phase 1 to Phase 2, in an attempt to stop Serbian paramilitaries from carrying out their outrages.

This was a role NATO air forces were singularly ill-equipped to perform. As Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff Army Gen. Henry H. Shelton would say later, “The one thing we knew we could not do up front, was that we could not stop the atrocities or the ethnic cleansing through the application of our military power.” At this point, it was clear that the plans of the Clinton administration and NATO leadership had been based on false assumptions.

NATO air forces could not actually attack the Serbian paramilitaries in the act of committing atrocities on the ground—atrocities are generally committed in intimate contact with the victims, and pilots flying at altitude cannot distinguish individuals from one another—so they turned their attention to the Kosovo-based Yugoslav 3rd Army, thought to be protecting the paramilitaries from KLA attack. Although NATO aircrew and intelligence officers thought they were doing substantial damage to the 3rd Army, it is now known that the difficulties of targeting and the widespread and clever use of decoys by the Serbs greatly mitigated the damage. To this point, Milosevic and his country were not only weathering the bombing with visible ease, but the lack of success and media images from Serbia and Kosovo were threatening to split NATO from within. According to Ivo Daalder in the postwar BBC production, Moral Combat: NATO at War, “There was a sense that in fact [Albright] had led the administration down this path and had failed. Madeleine’s War, as it came to be called, all of a sudden didn’t look so good.”

As an airman thoroughly trained and indoctrinated in the use of strategic attack, Short believed from the beginning that he should be allowed to go after a broad range of targets. On April 1, after a contentious, closed-door session at NATO headquarters, Short was authorized to widen the air war’s targeting priorities, but still not to the extent he wished: Aircrew could go after infrastructure and other targets south of 44-degrees north latitude—a line well south of Belgrade—but north of that line, targets were limited to C3 and government headquarters.

The expanded campaign failed to have the desired effect. The Serbian paramilitaries continued to drive out Albanians from Kosovo, and Milosevic showed no sign of acquiescence. Short believed political control over NATO was tying his hands with “lowest common denominator targeting,” where a single member country could object to a given target and keep it safe from NATO attack. Of one particular target, he was told by officers from a NATO ally, “Don’t even ask!”

Washington officials told Lt. Gen. Michael Short, “Mike you’re only going to bomb for two or three nights; that’s all the alliance can stand, that’s all Washington can stand.” Photo: DOD

TURNING POINT

By NATO’s 50th Anniversary summit in Washington, D.C., on April 23, the offensive was foundering. Between setting off the worst case of ethnic cleansing in modern history and the widely broadcast incidents of collateral damage, a full month of bombing had failed to do anything except weaken NATO’s moral case. Former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger said at the time that failure would “threaten the very essence of NATO,” while Daalder in his Frontline interview added, that if we lost the war, “NATO is ended, and the credibility of American foreign policy is at an end.”

Ironically, it was recognition of the threat to the existence of the alliance that ultimately emboldened NATO to make one more push to win the campaign.

According to RAND senior political scientist Benjamin S. Lambeth’s NATO’s Air War for Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment, the consensus from the Washington Conference was increased NATO willingness to attack major infrastructure targets. NATO’s Master Target File had started OAF with 169 entries; now it had grown to 976. “The new goal became punishing Belgrade’s political and military elites, weakening Milosevic’s domestic power base, and demonstrating by force of example that he and his fellow perpetrators of the abuses in Kosovo would find no sanctuary.”

Gen. Wesley Clark believed it would take at least three months to assemble 175,000 men in Albania to launch a ground invasion. This would have given Milosevic plenty of time to drive wedges deep into the alliance. Photo: SrA. Mitch Fuqua via National Archives

CRONY ATTACK

The gloves hadn’t come off entirely, but now a new strategy was implemented in the Allied Force planning cell. The Joint Warfighting Analysis Center in Dahlgren, Va., analyzed the Serbian levels of power and focused on recommending targets that would bring the war home to Milosevic and his benefactors on a personal level. According to USAF Maj. Julian H. Tolbert’s 2006 School of Advanced Air and Space Power Studies thesis, NATO was now engaged in a campaign of “Crony Attack.”

The idea, Tolbert wrote, was to coerce the regime’s key patrons into pressuring a change in policy. The trick, of course, was to find out who Milosevic’s cronies were and what pressure points they would be susceptible to. According to Major Tolbert, “Crony attack strategy relies primarily on intelligence. … A network of cronies must be carefully mapped out, and it must be based on the nature of the relationship with the leader to help determine how best to influence the regime.”

According to a 2001 MSNBC article by William Arkin and Robert Windrem, on the night of May 15, USAF B-2 bombers attacked a steel plant at Smederevo and the copper smelter at Bor in a classic crony attack. Both of these facilities were used by Milosevic’s benefactors to personally and illegally enrich themselves at the expense of the state. In a bold move, NATO information warfare specialists took the unusual step to contact the targeted cronies before the strikes, just to drive the message home that NATO could destroy their sources of wealth at will—and there was absolutely nothing they could do to stop it. While there were still more maneuvering and strikes to come, NATO had found its silver bullet. According to Daalder and the Brookings Institution’s Michael O’Hanlon in their postwar book, Winning Ugly: NATO’s War to Save Kosovo, the timing was perfect: “That escalation in the strategic air campaign came on top of earlier attacks against bridges, petroleum refineries, and other key infrastructure, which in turn came on top of years of sanctions against Yugoslavia. … Probably fearing that time would only work against him strategically from that point on, Milosevic relented.”

Infographic by Mike Tsukamoto/staff

THEORIES, ARUGMENTS, AND REVISIONISM

Almost as soon as the dust from the last NATO bomb had settled, alternative theories were put forward to explain Milosevic’s capitulation. Most of these (Russia’s decision to turn its back on Milosevic, easing of Rambouillet’s demands, etc.) are easily seen as being complementary to the bombing and not a substitute. But others (KLA attacks forced the Yugoslav Army to concentrate, making tactical bombing effective) are demonstrably false. One theory, however, has had sufficient weight put behind it that it has become almost conventional wisdom: Milosevic caved because he was afraid of an invasion by NATO land forces. Gen. Wesley K. Clark, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander, espoused this theory himself in his 2001 autobiography, Waging Modern War: Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Future of Combat.

However, there are a number of reasons why this is highly unlikely: First, Clark believed it would take at least three months to assemble 175,000 men in Albania to launch a ground invasion. This would have given Milosevic plenty of time to drive wedges deep into the alliance.

Second, the logistical problems were nightmarish. The only country willing to serve as the launch point for the invasion was Albania. Macedonia had pointedly ruled out an invasion from their soil, and Hungary did not want to give Belgrade any excuse to persecute ethnic Hungarians in the Serbian province of Vojvodina. Also, the sole road suitable as a main supply route through Hungary would have to be improved before it could support armored vehicles. Further, even the later insertion of UN-sanctioned Kosovo Force (KFOR) peacekeepers under truce conditions proved problematic. The senior British Army commander in KFOR reported that an opposed entry would have been “unworkable.” He reported back to London, “It is the view of this headquarters that had the situation on 12 June been anything less than benign, there would have been command, control, and communication difficulties which could not have been resolved by KFOR headquarters.”

Third, given the prevailing political climate, there is little chance NATO could have mounted a ground invasion. Several NATO member states were adamantly against it, and Germany’s Chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, promised to veto any invasion plans. France, Italy, and Greece also stood opposed to invasion and undoubtedly others would have followed their lead, had it come to a decision. The Pentagon was also against it. None of this would have escaped Milosevic’s attention.

However, the most important argument against the idea that the threat of invasion was the ultimate defeat mechanism is history itself. The heritage of the Yugoslav Army stems from their fierce guerilla war waged against the WWII Nazi occupation. VJ doctrine was to fight a delaying action against an invader to allow partisan forces to organize and arm themselves, eventually driving the invaders out. It cannot be overstressed how deeply this culture runs through the VJ—it is their identity.

Since neither the VJ, nor partisan warfare, could successfully resist an effective air campaign, their only hope of victory was to divide NATO politically or force NATO into ground combat where Yugoslav forces would have stood a chance. A NATO invasion would likely have done both. Sandy Berger, President Bill Clinton’s national security adviser, believed that debate over a ground war could have split NATO and handed Milosevic his only shot at victory. According to Berger, “An equally good school of thought says that Milosevic would have loved to get us into a ground war.” Russian President Boris Yeltsin claimed in his memoirs that Milosevic actually encouraged Russian Special Representative to Yugoslavia Viktor Chernomyrdin to conduct the negotiations in such a way that the ground operations would start faster.

In a postwar interview, Nebojsa Pavkovic, commander of the 3rd Yugoslav Army said that, “[NATO] would have lost any advantage [in a pure air campaign] the minute they committed their troops. …We knew the land, and we were well prepared in the event of the ground war. … We were not afraid of the ground war.”

Said RAF Air Vice Marshal Tony Mason: “[Milosevic] wanted a ground-force strategy. … Milosevic really wanted us to get into ravines and into gorges. He really wanted to relive the Serbian situation in the 1940s again.”Therefore, far from being intimidated by the threat of NATO ground troops, Milosevic and the VJ would likely have welcomed the chance to draw enemy blood on their home ground.

Coercion worked in Kosovo because NATO airpower could hold at risk things that the Milosevic government needed to remain in power. Contrary to popular belief, Milosevic was not a dictator, but rather the leader of a political coalition in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood. He and his party were actually at risk if the voters of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia became radically discontented. With effective economic sanctions in place, Serbia was diplomatically isolated and particularly vulnerable to strategic airpower and coercion. The price of noncompliance with NATO’s demands—somewhat softened since Rambouillet—was more than they could afford to pay.

CONCLUSIONS

The fact that airpower won NATO’s first war is indisputable. However, this victory was far from inevitable. Just showing up with a lot of airplanes isn’t enough, and in this case, risked shipwrecking an alliance that was the foundation of US and European defense policy for 50 years. Airpower must be wielded in an intelligent and appropriate manner to be effective, and its proper usage is not always intuitive. In Allied Force, much time and political capital were expended to no positive effect when the template for Operation Desert Storm was unthinkingly overlaid on Kosovo by government and military leaders unschooled in air operations. Further, the factors that made airpower so effective in OAF—diplomatic and economic isolation—may not be present in another conflict, so air planners cannot merely overlay the Allied Force template over every future problem.

Airpower is one tool in the nation’s foreign policy toolbox. It will be the preferred tool for some situations, and will be inappropriate for others.

Airpower should take the lead role in conflicts like Allied Force, while in others, such as the counterinsurgency campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, it can only be a supporting arm. However, airpower’s inherent flexibility and the fact that it can be employed without the intractable commitment required by ground forces can make it particularly attractive to politicians, even in situations in which it might not be the most appropriate tool. Therefore, Air Force officers must not only be masters of their trade in traditional usage, they must have the mental flexibility and creativity to handle complex problems not traditionally found in their wheelhouse.

William A. Sayers has master’s degrees in military studies and strategic studies from Marine Corps University. He spent 28 years as a military analyst at the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Counterterrorism Center, and the CIA.