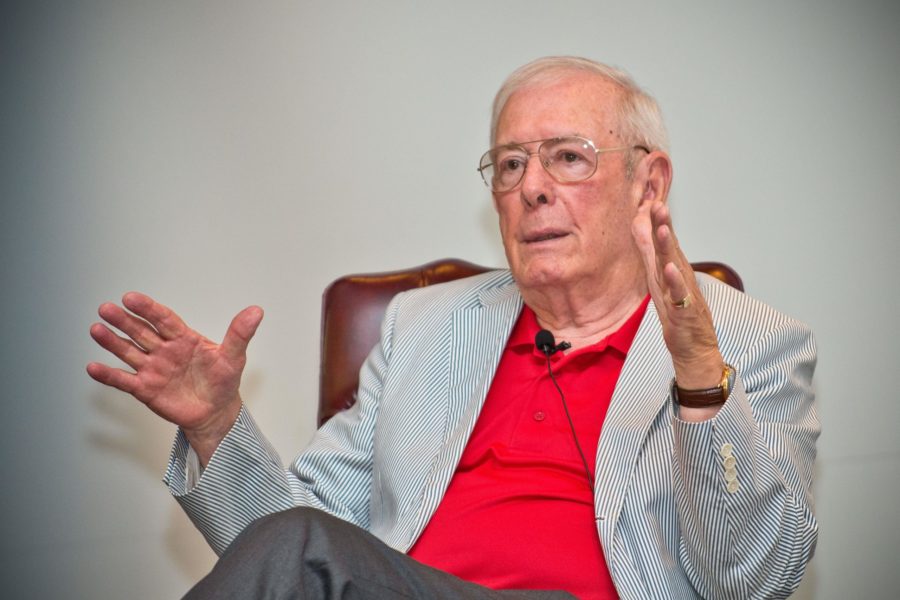

Gen. Charles G. Boyd, the only Vietnam-era prisoner of war to become a four-star general, died March 23 at the age of 83. Boyd was also a former vice commander of 8th Air Force, commander of Air University, and deputy commander of U.S. European Command.

Born in Iowa, Boyd entered the Air Force in 1959 through the aviation cadet program. He learned to fly the F-100 Super Sabre and F-105 Thunderchief, and was deployed to Southeast Asia in November 1965.

On April 22, 1966, Boyd volunteered for an unusually dangerous mission to attack surface-to-air missile sites around Hanoi, the North Vietnamese capital, in an F-105D. According to his citation for the Air Force Cross—the highest decoration after the Medal of Honor—Boyd, on his 105th mission over the North, bravely pressed the attack repeatedly through heavy enemy fire, including close calls with two SAMS. After repeated passes, he was hit. Ejecting at high speed, the force of the wind tore his helmet off, and shortly after landing in a rice paddy, he was captured.

Boyd spent the next seven years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese, enduring torture, brutal interrogation, solitary confinement, malnutrition, and illness. For 18 months, he was imprisoned adjacent to Navy flyer John McCain, who later became a U.S. senator and Republican presidential candidate.

Boyd was among the 50 or so prisoners forced to walk through the capital in the 1966 “Hanoi March,” a propaganda event in which downed pilots were humiliated and struck by civilians lining the march route, showing that Hanoi refused to be bound by the Geneva Convention banning such treatment.

Boyd was repatriated in 1973 after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. He resumed his Air Force career, taking four years to heal up from his injuries, earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the Air Force Institute of Technology, and attend the Air War College. Due to malnutrition during his captivity, Boyd’s eyesight wasn’t good enough to allow him to resume USAF flying duties, although he flew private aircraft for many years afterwards.

Over the next 12 years, Boyd rose rapidly through the ranks, holding staff and command assignments in the Pentagon and Europe. From December 1986 until June of 1988 he was vice commander of 8th Air Force; from 1990-1992 he commanded Air University; and in his last post he was deputy commander-in-chief of U.S. European Command, retiring in August 1995 as a four-star general.

Boyd remained an active voice in national security after his Air Force career. He served as a strategy consultant to Rep. Newt Gingrich, Speaker of the House; and in 1998, he served as director of the Hart-Rudman commission assessing U.S. security needs for the 21st century. Seven months before the 9/11 attacks, the panel presciently called for the creation of a federal department much like the eventual Department of Homeland Security to monitor terrorism and protect against it.

He later became senior vice president of the Council on Foreign Relations, as its Washington program director. He also worked as a director at various defense and intelligence-oriented companies, was CEO of the Business Executives for National Security, and was chair of the Center for the National Interest think tank.

Boyd wrote that fighter pilots were uniquely suited to endure the ravages of being POWs, as they were accustomed to facing battle relying almost entirely on their own wits and resources.

“It should not seem surprising that this breed of men would be as well-equipped as anyone to cope with the special problems of isolation,” Boyd said. The enemy “thought they could ‘divide and conquer;’ that without collective leadership we would not be able to maintain our resistance and resolve. But they did not reckon with the individual integrity of the American fighter pilot.” The endurance of American POWs in Vietnam is “a testimony to the individual spirit,” Boyd said. “We returned with our mental health …because the highest degree of achievement is possible only when man is imbued with a spirit of individualism.”

Air Force Association President, retired Lt. Gen. Bruce “Orville” Wright, said “Gen. Boyd was an inspirational figure, in his warrior spirit, his incredible endurance under brutal conditions, and his intellectual gifts to the national security community. An exemplary leader for generations of Airmen, he inspired us in every encounter.”

Retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, dean of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, worked for Boyd from 1988 to 1989 and remained in contact with him throughout his life. “Gen. Boyd was a giant of an Airman” who “exuded thoughtfulness in all the aspects of the word,” Deptula said. “From the perspective of complete evaluation of all aspects of a situation, to the empathy of man who had consideration for others’ perspectives. … He took me flying in his T-34 not that long ago, and he was at home in the air. May he Rest In Peace in his final resting place in the clouds. He was a true warrior, scholar, leader, Airman, and will be dearly missed.”